A family road trip to South Dakota raises questions about the line between vandalism and art.

Graffiti on the wall of the school. And the critics say, art, not so much.

When I dropped my daughter off at school last week, I noticed a giant multi-colored splotch of spray-painted graffiti on the school’s brick wall. It was unsightly and amateurish. Clearly, this was vandalism. Yet, there’s plenty of graffiti out there that you could easily argue is legitimately art. “Graffiti artist” is not necessarily an oxymoron.

In Boulder, there’s an artist named SMiLE who, under the cover of darkness, paints images of the Dalai Lama, Vincent van Gogh, and nameless cats in back alleys and on wooden fences and electrical boxes. He uses intricate stencils and layers of vibrant colors. Most Boulderites delight in his theoretically illicit work.

Graffiti or art? The work of SMiLE, who leaves his stenciled work in the dead of night around Boulder, Colorado.

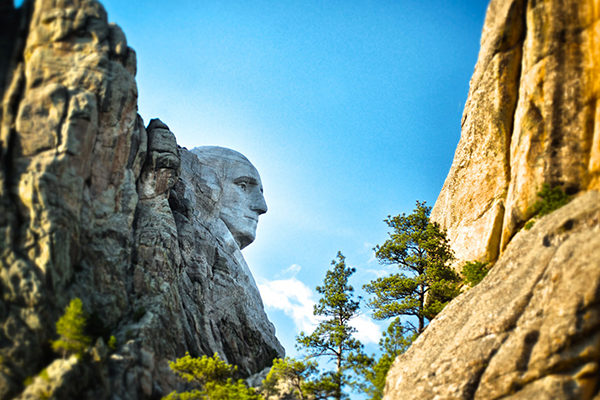

Boulder’s graffiti got me thinking about our big summer trip to South Dakota. On July 4, as we walked past the state flags fluttering in the breeze, framing the massive heads of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln, it occurred to me Mount Rushmore could easily be construed as federally funded vandalism—literally on a monumental scale.

If you look carefully, you can see a face in the rock. Photo by Ken Kistler.

I’ve always taught my kids that while in the wilderness, leave only footprints, take only pictures, and kill only time. And there we were in the Black Hills, surrounded by ancient mountains considered sacred by indigenous people, looking skyward at an epic defacement of a once pristine mountainside.

On the one hand, Mount Rushmore is indeed an amazing feat of engineering and artistry. The historic black-and-white photographs of workers in the 1930s hanging from leather harnesses and perched on wooden scaffolding, armed with chisels and sticks of dynamite, are nothing short of remarkable. Drawing on a technique developed by the ancient Greeks, sculptor Gutzon Borglund used a pointing system and a giant plumb bob to translated his 1:12 scale model of the presidents into 60-foot-high heads with 20-foot-tall noses and unsmiling mouths that span 12 feet across.

On the other hand, 450,000 tons of granite were blasted from the mountainside to create the monument. That’s not exactly leaving nature like you found it, now is it?

Mount Rushmore is impressive, as is the enormous pile of rock blasted off the mountainside. Photo by Heath Hughes/Unsplash

Instead of the usual July 4 fireworks, we watched the nightly lighting ceremony at Mount Rushmore. It included a film on the monument’s construction and historical background on each of the four presidents. It was all very patriotic. After the national anthem, my son turned to me.

“It’s propaganda, mom.”

The next day, we went back to the monument and caught a ranger talk by a Native American who happened to be the great grandson of Chief Red Cloud of the Oglala Lakota tribe, a leader known for confronting the U.S. government on issues surrounding land rights in the late 1800s. The ranger talk was a weird scenario, especially when juxtaposed against the previous night’s rah-rah rally for ‘Merica. This park ranger was on mission to bring a Native American perspective to visitors.

He told us the Lakota names of sacred sites renamed by the white man. He told us about the Native Americans relationship to the land—and how the Europeans had come and stolen it away. He didn’t sugarcoat anything. And he weighed in on Borglund’s handiwork, looming high over our heads, which 3 million people come to ogle at every year.

“The rock never should have been carved,” he said.

He showed us a picture of the mountain in its untrammeled form—and how you could see, if you looked just so, images of people and animals in the native rock. It was beautiful as it was, he said.

Three smiling faces at Mount Rushmore.

Mount Rushmore was carved in a different time, we reasoned. I’d like to think we’re more enlightened today. Such an audacious project would never fly in modern times. Right?

Well, next on our itinerary was a visit to Crazy Horse Monument. In what sounds like a case of justifiable one-upmanship, shortly after work began at Rushmore, Chief Henry Standing Bear asked another sculptor, Korczak Ziolkowski, to carve the image of an Oglala Lakota Warrior named Crazy Horse into the mountainside 15 miles from Mount Rushmore. “My fellow chiefs and I would like the white man to know that the red man has great heroes, too,” Standing Bear told the sculptor.

Demolition: The partially finished Crazy Horse Memorial. You can see the cranes and other machinery at work on top of the mountain.

It seems only fair that the Native Americans would have a monument dedicated to their people, too, but blasting a mountain to smithereens seems to contradict the reverence for the land that Chief Red Cloud’s great grandson had been telling us about the day before.

We paid the $30 entry fee to see the monument in progress. At the visitor center, there was a movie with cool footage of Ziolkowski starting the project in the 1940s. He ascended 700 rickety wooden steps up to drill and blast, and then descended the steps every time the generator went kaput. Like seeing the black-and-white photos of Mount Rushmore’s early days, it was fascinating to see these early images.

But it’s not just history. The Crazy Horse Memorial is unfinished and blasting and carving continues to this day. Ziolowski’s family continues the work he started. We could see the cranes and front-end loaders on top of the sculpture. Crews are currently working on the warrior’s pointing hand. Once completed, the memorial would stand 563 feet high, with an 87-foot high head. It will dwarf Mount Rushmore.

Our visit to Crazy Horse was another chance to wonder about the irony inherent in these mountain monuments. Thunderhead Mountain, the site of the Crazy Horse Memorial, is considered sacred by some Oglala Lakota. Evidently, Crazy Horse would never allow his photograph to be taken, so how would he feel about his image captured in stone? We wondered.

A model of the Crazy Horse Memorial shows how it will look when finished…if it’s ever finished.

We did our best to come to terms with the contradictions: blasting a mountain in the Black Hills that’s sacred to Native American people to create a monument to Native American people. And that this project is happening in the year 2018—at a time when I’m trying to instill the Leave No Trace ethic in my kids. I tell them not to carve their initials in trees or pick wildflowers or collect rocks.

And yet, we came home from South Dakota with rocks in our car. At Crazy Horse, you’re welcome to take home a free hunk of the rock blasted off Thunderhead Mountain. They’ve got tons of it.

Speak Your Mind